My M.Sc. research

2019–2021 • Organismic & Evolutionary Biology • University of Massachusetts – Amherst

My Master’s thesis centered on the global snow leopard population in Central Asia, where I learned firsthand the immense value of local knowledge, particularly in ecology. My collaboration with local conservation practitioners and organizations greatly enriched my understanding of snow leopard ecology, and helped me understand and appreciate the deep cultural and historical significance these animals hold within very remote communities in the region. This experience underscored for me the importance of embracing and valuing diverse perspectives in conservation science, especially those rooted in indigenous and local knowledge, which is often overlooked in ecology and in science more broadly.

My work focused on three projects:

1) Optimal sampling design for spatial capture-recapture: Monitoring populations is extremely expensive, and design protocols lack both statistical rigor and logistic flexibility. This framework directly addresses those issues through formal optimization, creating efficient designs producing more accurate estimates, which is especially critical for the conservation of rare and elusive species. (paper published)

2) Improved inferences about landscape connectivity from spatial capture-recapture by integration of a movement model: Methods describing landscape connectivity have long been confined to a single scale. This new model scales inference from individuals to populations, providing an unparalleled framework to understand how landscapes create emergent patterns of spatial structure in populations, with great potential for conservation planning. (paper published)

3) Developing data-sharing platforms for collaborative, range-wide analyses: Apex predators play a fundamental role in ecosystems, and there are many open questions about their range-wide, spatial-ecological dynamics. To address this, JAGSMAP is a data-sharing platform that brings together a trans-boundary network of jaguar biologists to address important challenges in jaguar ecology & conservation. (paper submitted)

Photo by Robert Sachowski / Unsplash

Birding and wildlife photography

My passion for research surely traces back to my early interest in birds. My deepest thanks goes to an elementary school teacher of mine who chose to teach her students about the natural world around us. Though I didn’t fully grasp the significance at the time, my public elementary school in Concord, Massachusetts was named Thoreau School, after Henry David Thoreau, the early American naturalist. Together, the town, and the way it embraces Thoreau’s work, as reflected in my teacher’s lessons, certainly nurtured my love for the environment. My interest in birds grew into my excitement around birding, which I combined with a simultaneous passion for visual art, which in my own way was also following in the steps of my parents, both journalists, who both have a calling for documentation and storytelling. Now that birding and wildlife photography are central to who I am, I have been fortunate to have opportunities near and far to capture some amazing wild animals – mostly birds, with other species as an occasional treat. During my time as an undergraduate at Cornell University, I gleaned as much as I could as a student at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, where I learned how to be an academic researcher. It was there, too, that I came to my love of quantitative ecology, which to me has just been another avenue for painting pictures of the world based on observation. This arch of my experiences has constantly brought me into nature and refined my observation abilities, which is always at the foundation of my research.

Red-headed Barbet, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Scarlet Macaw, Puntarenas, Costa Rica.

Northern Saw-whet Owl, Concord, Massachusetts, USA.

Golden-crowned Sparrow, Caramel Valley, California, USA.

Barred Owl, Concord, Massachusetts, USA.

Anna's Hummingbird, Sobranes, California, USA.

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona, USA.

Slaty Flowerpiercer, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Western Sandpiper, Vancouver Island, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Nashville Warbler (ridgwayi), Mount Rainier National Park, Washington, USA.

Hermit Thrush, Caramel Valley, California, USA.

Acorn Woodpecker, Pacific Grove, California, USA.

Black Turnstone, Pacific Grove, California, USA.

Buff-fronted Quail-Dove, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Black Phoebe, Monterey, California, USA.

Scarlet Tanager, Concord, Massachusetts, USA.

Dark-eyed Junco, Pacific Grove, California, USA.

Tree Swallow, Cape May, New Jersey, USA.

Canada Jay, Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontaria, Canada.

Long-tailed Hermit, Gamboa, Panama.

White-throated Sparrow, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Piping Plover, Revere Beach, Massachusetts, USA.

Silvery-throated Tanager, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Curve-billed Thrasher, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona, USA.

Snowy Egret, Everglades, Florida, USA.

Buff-throated Saltator, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Upland Sandpiper, North Dakota, USA.

Rufous Mourner, La Selva Biological Station, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Northern Fulmar, Iceland.

Chestnut-backed Antbird, PN Carara, Puntarenas, Costa Rica.

Prong-billed Barbet, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Violet Sabrewing, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Northern Jacana, Puntarenas, Costa Rica.

Baltimore Oriole, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Northern Saw-whet Owl, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Common Chlorospingus, Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Orange-crowned Warbler (lutescens), Mount Rainier National Park, Washington, USA

Travel

I am extremely appreciative of the opportunities I’ve had to travel around the world. Some highlights include Panama, Iceland, Costa Rica, the United Kingdom, and throughout much of the United States. These experiences have left a major mark on my research, having seen just some of the great variation that exists among environments around the world. Iceland opened my eyes to the evolutionary success of orchids after I found a Leafy Northern Green Orchid (Platanthera hyperborea) in the Westfjords, growing at almost the maximum latitude for the Orchidaceae family in a region that has some of the harshest winters anywhere. In Snæfellsjökull National Park, just the next day, I spotted my first Arctic Fox, an animal I had dreamed of seeing since I was a child. Costa Rica and Panama, of course, were both overwhelmingly exciting for me given the massive diversity of bird species, from a Scaly-throated Leaftosser at Sendero La Laguna outside Gambora, Panama, to the endemic Coppery-headed Emerald in Costa Rica. These travels, rich with flora and fauna, serve as both a reminder and an inspiration of the vibrant biodiversity that fuels both my passion and my studies.

Logan Pass, Glacier National Park, Montana, USA.

Leafy Northern Green Orchid (Platanthera hyperborea), Westfjords, Iceland.

Pipeline Rd., Gamboa, Panama.

Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.

Large Whorled Pogonia (Isotria verticillata), Acton, Massachusetts, USA.

Montana, USA.

View from Going-to-the-sun Rd., Glacier National Park, Montana, USA.

Eno Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Buffalo Jump, North Dakota, USA.

Panama City, Panama.

Lake Carnegie, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.

Punta Culebra, Panama.

Rio Grande, Carson, New Mexico, USA.

Crocodile Bridge, River Tarcoles, Puntarenas, Costa Rica.

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Southern region, Iceland.

Alajuela, Costa Rica.

Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.

Going-to-the-sun Road, Glacier National Park, Montana, USA.

Going-to-the-sun Road, Glacier National Park, Montana, USA.

Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.

Jacques Cartier Provincial Park, Quebec, Canada.

Trichocentrum lacerum, Barro Colorado Island, Panama.

Westfjords, Iceland.

Heath Spotted Orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata), Western Region, Iceland.

Purple-ring Topsnail (Calliostoma annulatum) Monterey, California, USA.

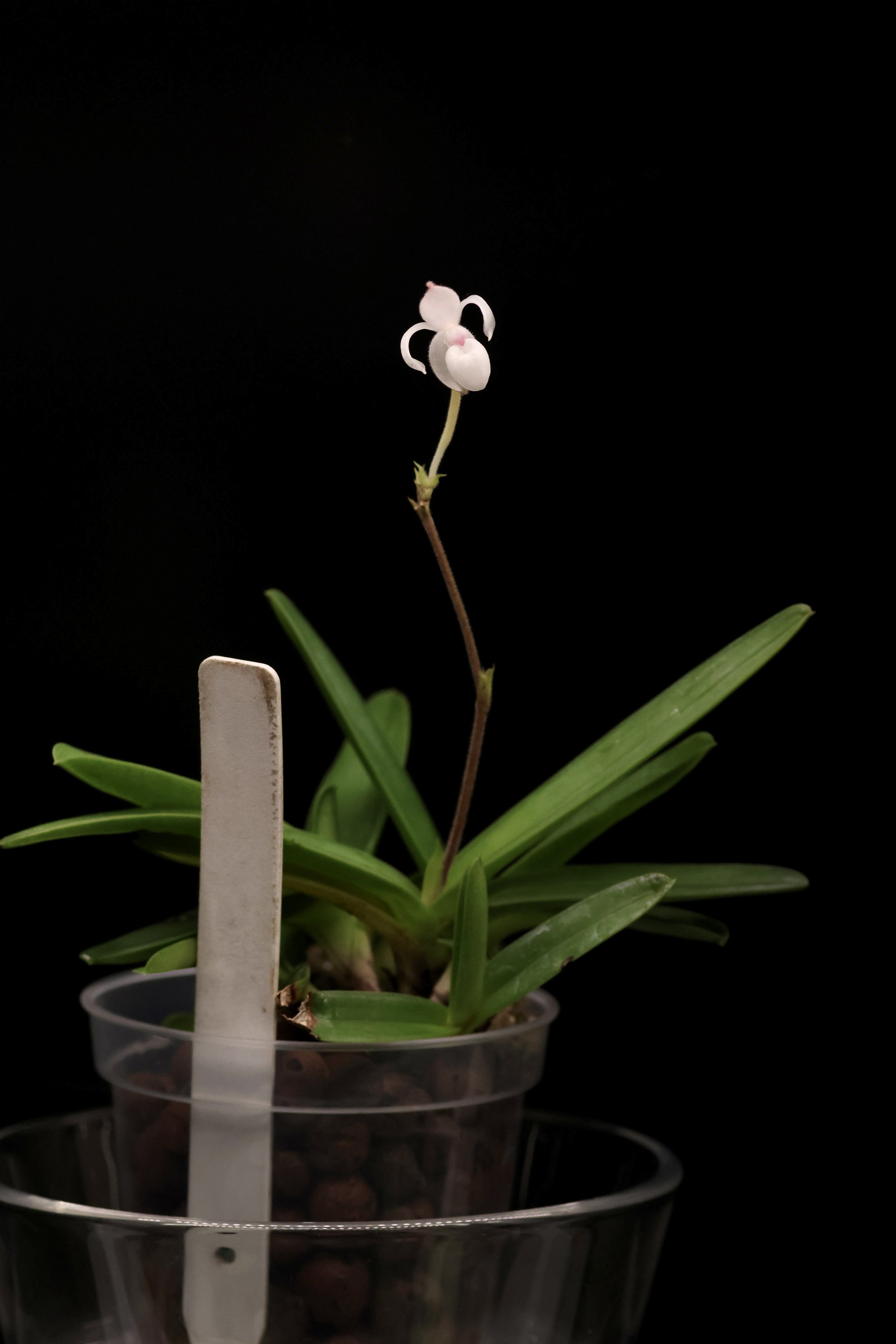

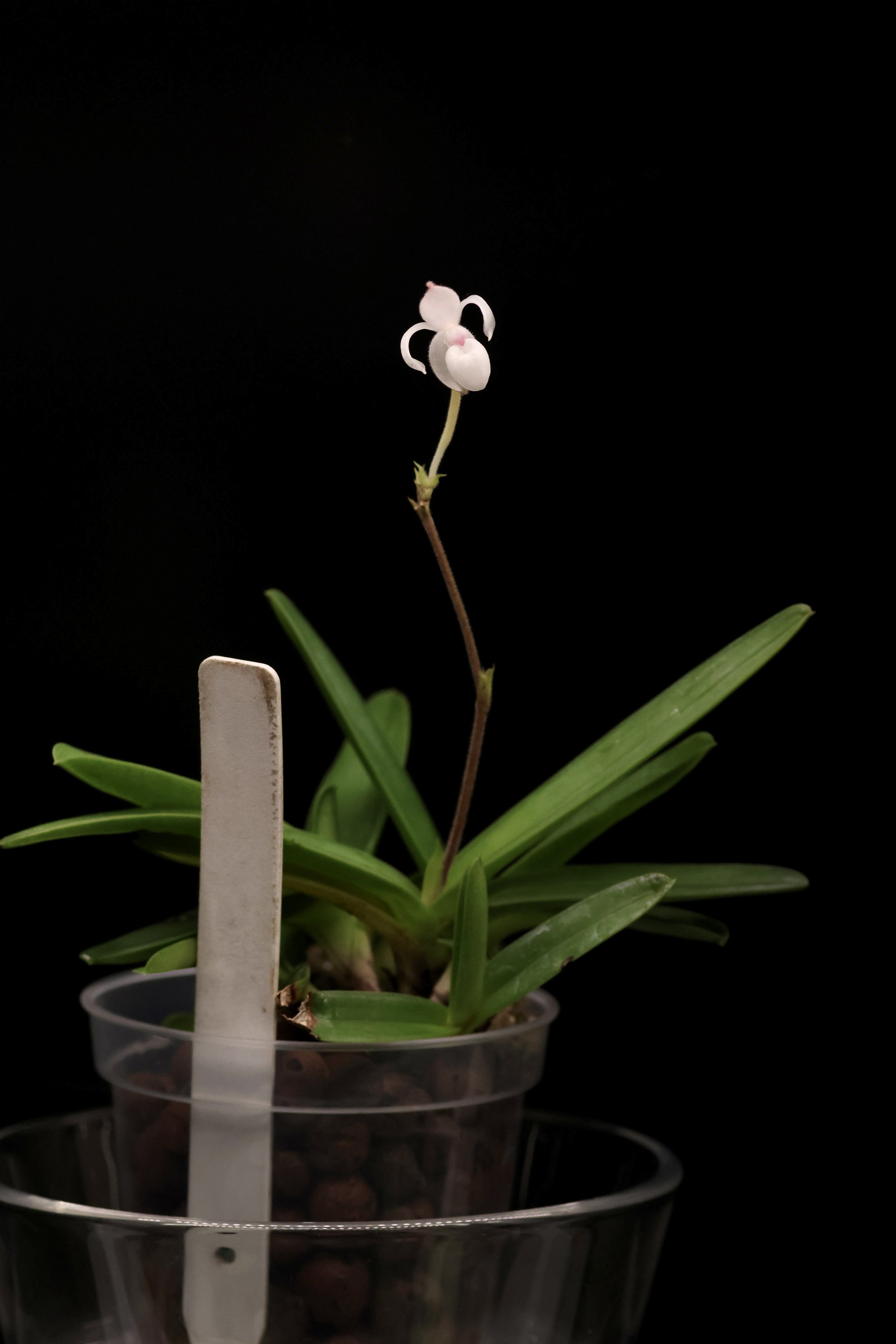

Cultivating rare orchids

Much like how 1 in every 10 species of vertebrate is a bird, 1 in every 10 species of flowering plant is an orchid – but there are three times as many species of orchids as there are birds! There are around 11,000 bird species and nearly 35,000 species of orchid, with about 10,000 of those orchid species hailing from the tropics. I love orchids, and I’m not alone – its thought that the features characteristic of almost all orchid flowers, such as bilateral symmetry, looks vaguely enough face-like that is elicits a certain response in people that makes us feel like we can relate to them just a little more than other flowers. All fun facts to remember next time you steer your cart past the Phalaenopsis plants at Trader Joe’s or your other local supermarket!

One of those Phalaenopsis plants was my first orchid when I was 12 years old, which a neighbor gifted to me. I latched on to this family of plants. I think they have always felt bird-like in spirit, with so many species and such variety and bright colors and unique ways of persisting and flourishing all over the world. Since then, my collection has grown quite a lot, and for the past decade I have focused specifically on cultivating rare orchids – species that are less commonly grown in the orchid trade, or species that are common in the trade but are nearly or likely extinct in the wild. Through growing these plants I have learned so much, especially in building an intuition for what plants need in different habitats around the world, what the distribution of those habitats looks like spatially as well as temporally as orchids have evolved, and helping me see how species interact in the geographical ecology of this massively diverse family of organisms.

All of the individuals in my collection are grown from seed in a lab. When pollinated, a single flower can produce anywhere from a few thousand to a few million seeds, depending on the species. As a result, it’s fairly easy to very rapidly multiply progeny and continue preserving a species in cultivation. This massively reduces the number of plants that need to be taken from the wild. Unfortunately, overexploitation is nevertheless a massive problem for orchids, and has lead to the total extinction of very many species. It’s a complicated topic, but keeping only plants grown from seed in the lab is orders of magnitude more sustainable than purchasing wild-collected individuals.

Some favorites in my collection are Dendrophylax lindenii, the Florida ghost orchid, which is an entirely leafless species endemic to the state and its swamps. I still remember the website where I first learned about the species – the Oak Hill Gardens website – which sold tiny seedlings on small twigs for around $25. This was probably my first step into my interest in cultivating highly-specific rare species. Since then, I’ve specialized in Phragmipeidums, rare varieties of Cattleya species, and Angraecoids.

Phragmipediums are a genus of mostly ground-dwelling orchids in Central and South America that grow in spots where their roots are constantly in touch with flowing water, which is a challenge hard to replicate in cultivation.

Cattleyas are a genus of large-flowered epiphytes from the same region, but in a wider variety of habitats, which in the 1900s were the typical flower for corsages. Though most Cattleya species are very common in the trade and in nature, there are some lineages that have unique periwinkle-colored flowers, said to be blue, and termed “coerulea” – these are my favorites.

Finally, Angraecoids refer to species in the subtribe Angraecinae that are native to southern Africa, Madagascar, and other nearby islands. These typically have flowers that are white with hints of copper and rose-gold coloration, which is a treat. The flowers remind me of Dendrophylax, which are actually closely related: Dendrophylax species across Florida and the Caribbean trace back to a common ancestor that made it all the way from Africa likely carried by the wind, and all 12 modern species are leafless, which is very strange and super fascinating.

As I continue to nurture and expand my collection, each orchid offers a window into the natural world's complexity and the endless wonders of ecology and evolution.

Aerangis punctata.

Phragmipedium besseae.

Mexipedium xerophyticum.

Laelia sincorana.

Lycaste aromatica.

Mexipedium xerophyticum.

Phragmipedium ecuadorense.

Cattleya percivaliana "Centro Remolacha".

Disa uniflora.

Phragmipedium Nichoelle Tower.

Dendrobium officinale.

Stanhopea nigriviolacea.

Neofineta falcata "Manjushage".

Phragmipedium ecuadorense.

Paphiopedium armenicanum.

Dendrobium cuthbertsonii.

Phragmipedium manzurii.

Angraecum urschianum.

Paphiopedilum braemii.

Laelia alaorii v. orlata.

Prosthechea cochleata.

Phragmipedium ecuadorense.

Spiranthes cernua.

Paphiopedilum braemii.

Platystele repens.

Laelia alaorii v. orlata.

Cattleya percivaliana "Orchid Ranch".

Angraecum didieri.

Phragmipedium ecuadorense.